(T- 57 mins)

As I type this, 4 astronauts are preparing to be launched into space (if interested, look up the NASA SpaceX Crew-5 Mission). Times like these, you wonder at the beauty that is science. I’ve spent my life being fascinated by stuff like this, but that is not what I want to talk about today.

(Source- NASA livestream)

(Source- NASA livestream)

Off late I have been thinking more and more about what science really is.

For a world that is tipping towards ‘evidence-based’ everything, that glorifies ‘scientifically proven’ data and information, it is essential to understand what exactly is science and why has humanity’s focus shifted so drastically to all things science. And so, with that agenda in mind, I lost myself into a rabbit hole of history, philosophy, arguments and counter-arguments.

(T-47:51 mins; final checks being completed; yes I am going to write this as I also watch the launch proceedings :D)

It would be fair to start with the disclaimer that since ‘science’ itself is such a broad term, to expect it to have a standardized definition and understanding that covers all of its various facets and nuances would be preposterous.

(T- 44:37 mins; crew access arm removed from the Dragon)

There are 2 broad arms of science. The type of science that helps you build rockets like the Falcon 9, and surgical procedures for knee replacement, is called ‘applied science’. There are scientists that believe that that is the primary purpose of science- to acquire knowledge that has practical application (in creating tools, medicine etc), regardless of whether the knowledge itself is objectively true or not. This view is called ‘instrumentalism’.

The other group scoffs at this seemingly limited view of science, and is somewhat marred by superiority in that it strongly believes that science is about finding the ‘objective truth’ of the world. This is termed ‘realism’.

For the longest time, I have aligned the realist’s view of science, and do so now as well. But how exactly do we achieve this bold ambition? Have we gotten any closer to the objective truth? Does one even exist?

(T-35 mins; fuelling of Falcon 9 initiated)

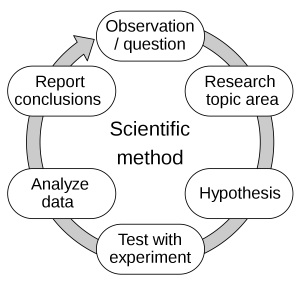

This is where the Scientific Method comes in, something that is considered superior to any other form of investigation. Essentially, it is a chain of steps scientists follow to ask and answer questions and it goes like this:

Inherent to the scientific method are the acts of observing and interpreting phenomena that occur. And both these processes, for humans, require perception and cognition.

Consider this.

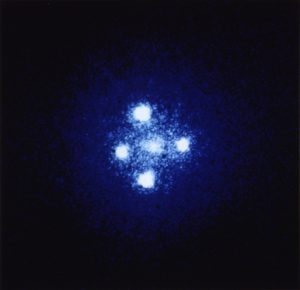

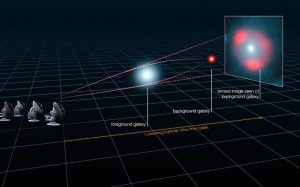

This image illustrates what’s called an Einstein’s cross. If I were to ask you how many objects you can view here, the logical inference would be that there are 5 different objects here. This assumption will be completely logical given the data you have, and your current knowledge. However, thanks to Einstein, we now understand the occurrence of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. Essentially, gravitational pull from extremely large celestial bodies like large stars, galaxies etc, bends light such that the objects right behind appear as a ring or cross around the central large body. So the 4 impressions around the central object actually belong to a single body, in this case, a quasar.

(Source: ALMA (ESO/NRAO/NAOJ), L. Calçada (ESO), Y. Hezaveh et al.)

Until Einstein enlightened the world with this new understanding, a scientist’s interpretation of the very same image would have been extremely different.

Apply that analogy to the studies of today. Our observations and inferences of the experiments we conduct today are limited by our current beliefs, understandings, and our imagination about the universe. There might be evidence right under our noses that we might be blinded to because we do not know we need to look for it. It is a common saying is medicine—‘the eyes only see what the mind already knows’.

Relativism thus seems very possible- the idea that ‘knowledge, truth, and morality exist in relation to culture, society, or historical context, and are not absolute’. Does this then bury our hopes of unearthing ‘the truth’ of the universe? Maybe.

Another aspect of science to pay attention to is exactly how do we reason as scientists? A lot scientific theories are inductive, in that we study certain phenomena on a sample, trying our best to make the sample as representative of the entire population as possible, and then we extend our results to be applicable to the entire population.

The heart of inductive reasoning is that- what happened in the past must be able to predict what will happen in the future.

(T- 13:05 mins; waiting for countdown)

You can clearly see the fallibility of this assumption.

Karl Popper, a well-recognised 20th century philosopher tried addressing this issue. He was a very ardent proponent of the distinction between science and pseudoscience, the major difference, according to him, being that while pseudoscience attempts to look for confirmation of a theory, science attempts at falsifying a theory. In his view, if you are looking for confirmation, you will find it everywhere; but if you are looking for evidence against something, and fail to find any, it strongly supports your theory. So in essence, Popper is where the idea of p-value first originated in its principle.

(T-3mins; I’m all pumped)

While the idea seems elegant, and admittedly, it feeds your moral superiority, it is not devoid of shortcomings.

(T-1mins; brb gotta watch the launch)

(T+ 0:35 mins; all seems good :D)

Since I am a medical student, I can clearly see how Popper’s philosophy of science can be problematic. Amongst other arguments, one I would want to highlight in this article is the fact that absolute truths really do not seem to exist. That ‘all A’s are X’s’ is a statement that is rarely applicable to real life subjects. While multiple genes are implicated in causing Type 2 Diabetes, it does not mean that every single person who has those genes will develop diabetes, because multiple factors contribute to the development of the disease.

(T+9:31 mins; Falcon 9 landed on droneship safely)

Even if we try to account for every single one of those factors; a) it is a near impossible and completely impractical task given the sheer number of these variables and b) we still might be unable to account for any new developments in the future that we do not understand yet.

Moreover, no theories exist in isolation. At the very least, there are certain assumptions that we must take as universally accepted truths for us to base our theories upon. So when we do find evidence possibly contrary to the theory, our first task is to determine whether the theory itself is flawed or is there are problem with the accompanying assumptions that we made. More often than not, we try to adjust our assumptions first before questioning an already accepted theory.

Let’s understand this with the example of Uranus’ orbit. Even with Newtonian Physics, the calculated orbit of Uranus did not match its actual orbit. Adams and Leverrier, assuming Newtonian Physics to be correct, independently hypothesised that these findings could be explained by the existence of another planet (undiscovered till then). In fact, they calculated the exact location of this planet using Newton’s laws. Neptune was only later discovered by Galle, and he confirmed its location to be exactly where Adams and Leverrier had calculated.

Popper touted this as an example of a ‘critical test’ passed by Newton’s theory i.e., it held even in the face of risk. But, what would have happened if Galle did NOT find Neptune? Would we have discarded Newtonian Physics immediately? Couldn’t Galle’s failure not have been attributed to other factors like faulty instrument, interference from other sources etc?

Imagine that world, without Newtonian physics- one without cars, and buildings, and humans going into space (who are all currently doffing out of their suits and getting off their seats btw).

One of the things that Popper did get right though is the fact that a scientific theory only holds true until evidence to the contrary is found. Science is NOT absolute. Our understanding of the world is constantly evolving, and at the heart of scientific questioning is to keep questioning our current theories.

One thing that I aim to achieve with this page is to drive home this message that, contrary to how media tries to portray it, and how most people fathom it, science is not some miraculous understanding of the world.

Nothing is truly ‘proven scientifically’ in that it becomes the absolute, irrefutable truth. When you read articles that refer to scientific studies that ‘find evidence’ or ‘positive correlation’ between 2 things, interpret it as a sign of possible linking of the 2 things, always remembering that-

- That association is only statistically significant, not 100% (possible future post about what it actually means)

- Correlation does not mean causation- just because A follows B, does not mean A caused B

- There are many more factors at play that the study hopefully tried to standardize, but that would play significant role in real life.

Treat science as what it is- one of a number of ways we try to make sense of the world around us, and a system that is constantly adapting to improve on its agenda.

Hope this article benefited you in giving you a peep into what science truly is. Would love for comments and feedback/suggestions in the comment box underneath this post.

3 Comments

Pacho herrera · October 5, 2022 at 10:42 pm

Wohooooooo

Shweta Deshkar · October 6, 2022 at 3:16 pm

Mind-blowing, insightful!

Mridula · October 6, 2022 at 8:01 pm

Thank you so much!